Cities ‘don’t fulfil potential’ for mental wellbeing

Mental health issues are on the rise with the urban environment increasingly thought to have a negative impact. As cities in the North West get busier, bigger, and more developed, what can be done to make them more bearable?

Manchester-based landscape architect Owen Byrom has some ideas.

He established Headplace, a privately-funded research project, in 2018, in order to gather information and present his proposals to alter major “pain points” in Manchester.

Headplace is in part an extensive research project which centres around plans to make Piccadilly Approach, Piccadilly Gardens and Market Street more inclusive for people who suffer from mental illness.

The project was developed with anxiety-based disorders in mind, as he found that “anxiety is the most common disorder.” However, he also considered ideas based on emotional and suspicion-based disorders like depression.

As arguably one of the busiest areas in Manchester’s city centre, which can be a triggering experience for people with anxiety, Byrom noted Piccadilly Gardens’ surprisingly positive historic link to mental health.

Urban Mind prompts users for their emotional responses throughout the day

“Piccadilly Gardens already has a strong connection with mental health. Before it was the public space we know today, it was the site of a psychiatric hospital. The old gardens were once walked by the patients of the hospital in order to alleviate their symptoms.

“The area currently ranks second on the most uncomfortable spaces in Manchester. The space is dominated by transport stops, irrationally placed interventions and a poorly maintained series of laws.

“Despite already including both blue and green spaces, the configuration of the space does not have any major benefits and does not fulfil its potential,” he said.

Byrom looked to many similar research projects in order to create alternative designs for Piccadilly Gardens.

One such example is Urban Mind, which collects and measures the effects of both urban and rural surroundings on mental health.

The app prompts the user to input how they feel in their location three times a day for two weeks. At the end of the trial, users receive a report summarising their experiences.

The app shows how people can be impacted by access to green and blue infrastructure, seating areas and easily navigable walkways.

According to Andrea Mechelli, a professor of early intervention in mental health at King’s College London, and one of the creators of the app, aspects which should have a positive impact can have surprisingly negative effects on people.

“You think putting in a park should immediately make people feel better; after all it provides access to green, and possibly blue, infrastructure, and connotes happiness. However, if the benches are positioned in a way that doesn’t provide enough shelter or privacy, or too much, and the walkways are narrow, and it’s by a school so it’s busy or provides a thoroughfare for students, this can make what should be a positive experience into a negative one for people.”

He went on to say: “It’s about understanding and measuring the impact of spaces, like cherished spaces” and then relaying that information back to “local communities so that the positive spaces, those which promote social and health value, can be protected.”

A collection of images people who use the Urban Mind app have uploaded which trigger anxious feelings

The data Urban Mind collects is utilised to inform planning and design for the public realm. The team is currently working with housing associations to develop methods to counteract negative effects.

Centric Lab plays a similar role, and was established to use neuroscience to make healthier habits for human life.

The company helped produce a ‘Neuroscience for Cities Playbook’ in collaboration with Future Cities Catapult and University College London. This aims to “provide solutions to mental and physical health challenges in cities, which is crucial for economic development”.

The solutions, tools, methodologies, and strategies put forward in the framework are intended to show how organisations can both use the research to better themselves, and to make financial gains, by creating comfortable environments that residential and office tenants alike want to stay in.

Centric Lab researchers looked into variables such as how cities are arranged, called ‘space syntax’, and applied mathematic models in order to predict the movement of people through spaces. This aims to show how future cities could be better designed to suit people.

Using research such as this, Byrom’s Headplace has created alternative designs for Piccadilly Gardens.

As it stands, Piccadilly Gardens has two Metrolink stations, Market Street and Piccadilly Gardens, and the Piccadilly Gardens bus interchange. It also has blue infrastructure such as fountains and a large water walkway, which people do use, but which has a four-foot drop around its edge to allow for water drainage.

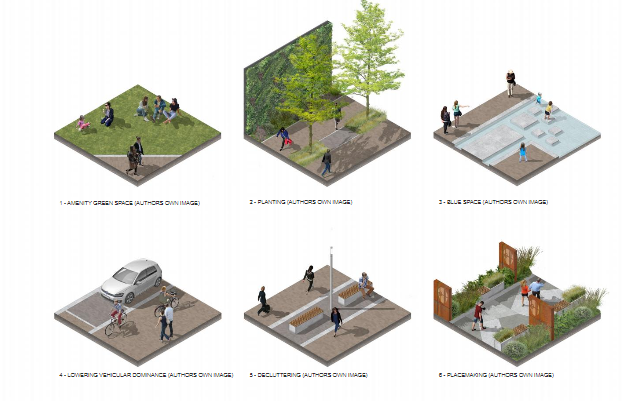

Byrom proposed four major changes, which fall under the categories of movement, space provision, blue space, greening and decluttering.

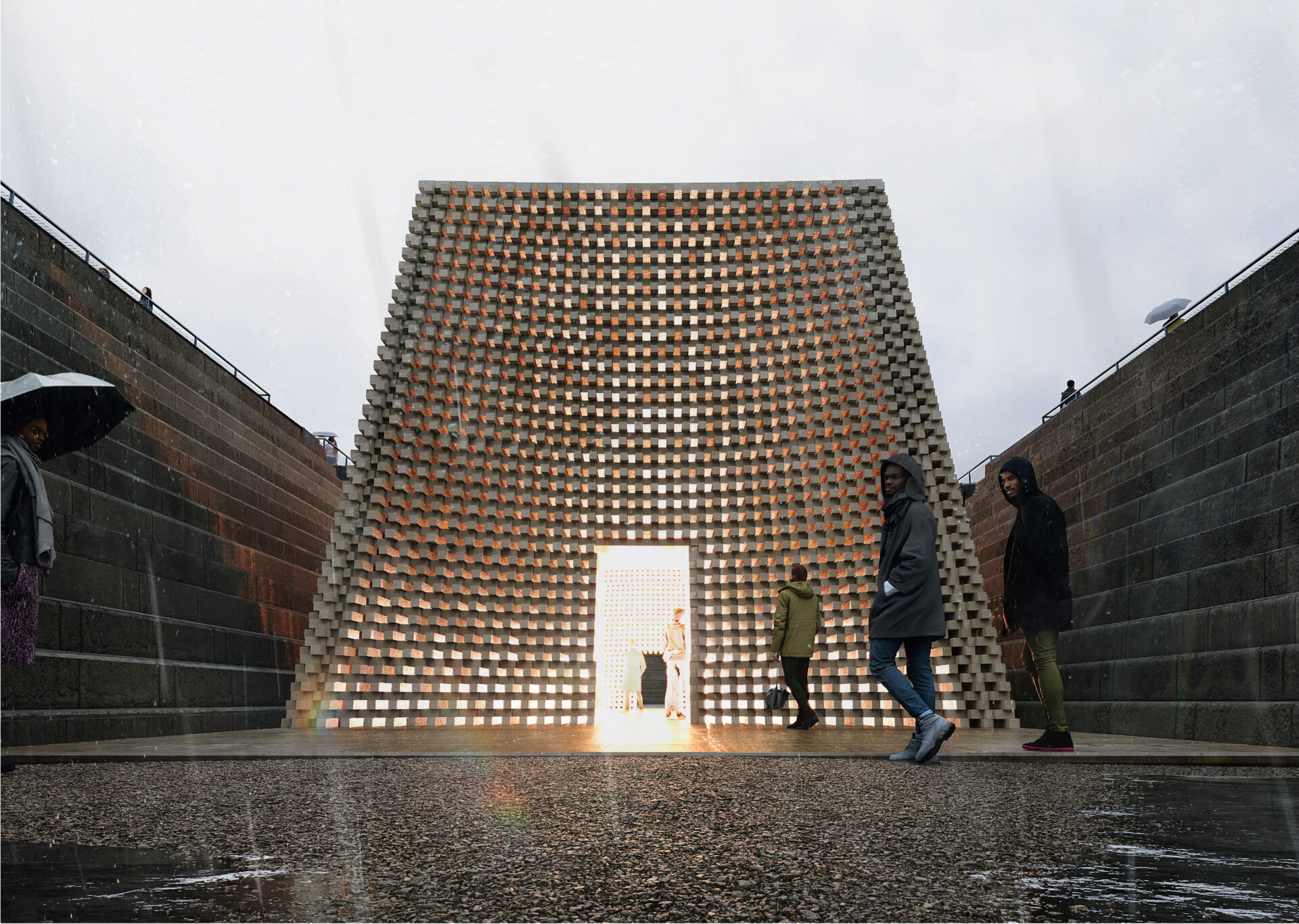

Byrom’s recommendations to make the space more suitable for people with anxiety

For movement, Byrom argued as Piccadilly Gardens is dominated by vehicles, that removing them would allow walkways to flow through uninterrupted.

For space, by using a ‘desensitisation toolkit’, Byrom offers a variety of spaces so the user can choose an area to suit their needs. He hoped sufferers “would start to engage with the space by using the smaller or individual spaces on offer at first and then moving into the larger spaces.”

“Fountains and other water-based infrastructure have been proven to be beneficial for an individual’s mental health”. By including a wider range of interactive and passive water features within the gardens, it could prove positive for interaction, animation and alleviation.

Transport stops and other clutter “litter” the space, and by removing them, it would allow for more green infrastructure up to the thresholds of the surrounding buildings. This would allow the space to meet its biophilic potential. The green space would be a mix of amenity and planted areas, and would make the space more immersive.

According to Headplace research “it only takes a ratio of 28:72 green to grey space to make a notable improvement to mental health.”

The impact of change with increasing urbanisation will be felt by all. Kevin Horton, architect director at K2 Architects in Liverpool, thinks that change is the trigger which will make people both with and without mental illnesses disconcerted in the urban realm.

“Immobility is safe as people actively want to do nothing, it’s the great paradox. The recent amp up of change in cities, including developments in technology and sustainability, have changed the standard cityscape.”

In his opinion, this is why people seek solace in the countryside, as it’s traditional, and not moved or changed by human interaction.

“The countryside is a safe space against the city. Nature is perfectly sussed out while the layout of the city is haphazard and chaotic, and that’s one of the reasons nature is such a more interesting concept. It has a calming influence because of the way things interact and integrate with each other.”

This is why, on a K2 project in 2016 for a nuclear power plant in the Lake District, the designs make the building appear to merge into surroundings. Unfortunately, the building was never delivered as the overall project was not progressed.

Moorside was designed based on an oil painting “to emotionally connect landscape with design” according to Horton

Horton said the project drew inspiration from the work of William Wordsworth, a poet deeply associated with the Lake District, and William Turner, an artist who blended elements of the industrial revolution with the natural landscape.

“We connected through a very poetic approach by creating the designs through the language and art of the landscape. We decided to use a very expressive approach to capture the colours of the mountainside and the movement of the fading heather in autumn with the russet and gold.”

The colours were intended to blend into the surrounding mountainous and trees. It also considers colour theory, which looks at the link between colours and mental health.

Horton incorporated these ideas into designs for a community centre in Bolton. In his initial consultation stages with the people who would be using the centre, he transcribed their comments and created a two-pronged base of what public infrastructure should be centred around.

The first was social activity, which includes space for leisure and a café, recognising the long-standing link between physical activity and mental wellness.

The second was social advocacy, which means helping people with basic needs. This includes access to Citizens Advice Bureau or a food bank and the like.

“To unite these two branches, we wanted to create a space for people to feel comfortable. That’s why we removed the reception desk from the entrance and in its place put the kitchen table. That immediately establishes the centre as more relaxed and welcoming and doesn’t place people in positions of power or lack thereof.”

For Horton, the garden was another way to incorporate this idea of subconsciously making people comfortable, thus lessening any triggers or creating anxiety. “When you’re a kid, you seek out corners because they fascinate you and they keep you safe. That’s why we navigate towards them and why homeless people seek shelter in them. They are also a place to hide.”

The work of people like Byrom and Horton show that attitudes towards mental health have changed in recent years; it’s not just utilisation of space but the feeling in the space which has become important. With 68% of the world’s population projected to live in cities by 2050, mental health needs to become more of a factor in designing these cities of the future, to avoid creating a mass of unhappy inhabitants.

Piccadilly Gardens is perfect, all walks of life, if you want to sit on the grass you can sit on the grass, if you want to enjoy a cider go ahead and enjoy a cider, if you want to mug a tourist at knifepoint, feel free, it’s all things to all people.

By P Karney

Excellent article. This is essentially a planning issue so it’s vital that the creation of healthy environments is integrated into planning policy, particularly in Manchester where planners and councillors do not appear to understand the value of good design at local neighbourhood level. It’s only ever used as a marketing tool or to obtain funding; beyond that it’s lip service.

By Richard Roscoe-Bartoli

Great article. Surprised this hasn’t had more comments – this issue is the nub of most of the vitriol on here directed at new developments in Manchester city centre (justified vitriol, usually!). There needs to be a concerted effort to consider the liveability of places as part of proposals – we as property and development professionals have a responsibility here, and its one that most of us shirk…

By Shirker

Piccadilly Gardens sums it all up.

By Liver guy