IN FOCUS | Will the great HMO clampdown make the housing crisis worse?

A growing number of councils across the country are putting measures in place to curb the development of houses in multiple occupation amid concerns about their impacts on residents and local communities.

While popular with owner-occupiers and a sure-fire vote winner, the measures could serve to widen the ever-increasing gap between market rents and local housing allowance, shrinking the pool of housing options available to some of the nation’s most vulnerable groups.

In September alone, Sefton, Hartlepool, Tameside, Chorley, Oldham, Liverpool, and Durham councils made moves towards tighter HMO controls.

They have joined many other councils such as Salford, Leeds, and Bolton with existing HMO controls in a bid to address the higher levels of crime and antisocial behaviour that they say this type of shared housing provokes.

Strain on public services, pressures on parking provision, and increased noise are also regularly reported in areas across the country with high concentrations of HMOs.

As a result, HMOs suffer reputationally and councils are acting en masse to close the planning loophole that allows for regular family houses to be converted into shared housing without having to go through the planning process.

A 15-year problem

The requirement for planning permission for HMOs for up to six people was removed under the watch of then-secretary of state for housing John Denham a month before Labour lost the 2010 general election.

The view was that having to obtain planning permission for this type of development amounted to an “unnecessary regulatory burden on landlords and local authorities” in certain areas, the government said at the time.

To its credit, the government also recognised that while some areas needed more HMOs to provide housing for people on lower incomes, there were others, like student cities, that would need a mechanism to prevent against an oversupply.

This is where Article 4 directions come in. The Article 4 is a tool that allows a council to remove permitted development rights in a given area and force developers to obtain planning permission for their projects.

The idea in the case of HMOs is to give local authorities more control over where this type of accommodation is delivered, thus mitigating against its unwanted side effects.

In practice, it works like this: if Salford City Council’s planning department deems that an area of the city already has enough HMOs, then it could refuse a developer planning permission.

Between the 25 of August and 5 October, Salford City Council did just that, rejecting nine applications or requests for certificates of lawfulness for small HMOs.

Without an Article 4, Salford would have been powerless to stop them.

Many cities and towns have been blocking permitted development rights for HMOs for more than a decade.

The Article 4 was once the preserve of student towns and cities. Many of them moved quickly following the 2010 change in planning rules to stop certain areas being overrun by students.

This was reflected in the immediate months and years following Labour’s 2010 rule-change when a glut of councils availed themselves of Article 4 directions. Among them were the student hotbeds like Sheffield and Newcastle.

In recent months, the number of councils proposing new or expanded Article 4 zones has soared and become decidedly less studenty on the whole.

The rising number of councils seeking to limit HMO development adds to an already difficult landscape for landlords.

High interest rates, looming deadlines around energy performance ratings, and the prospect of new laws being passed to beef up renters’ rights are prompting buy-to-let landlords to either sell up or carve up their assets into HMOs.

Some have termed the rising number of landlords exiting the market as a mass exodus but that might be overstating it according to Meera Chindooroy, the National Residential Landlords Association’s deputy director of campaigns, public affairs, and policy.

“A mass exodus is not accurate but there are some landlords choosing to leave the market,” she said.

Councils will point to the rising numbers of landlords selling up and call it a success; they regularly cite rogue landlords as a motivating factor behind their HMO clampdowns.

Chindooroy suggests that, while there are undoubtedly some bad actors in the sector, it is a case of a few bad apples rather than a whole cart of rotten ones.

“HMO landlords in general do provide a good service,” she said.

Sophie Lang, an executive at Propertymark, a professional body for property agents, said in many cases councils are implementing Article 4s to ease workload.

HMO landlords are required to comply with a set of rules that govern things like waste management. It is incumbent on councils to ensure these rules are being followed and that rogue landlords are weeded out.

However, a lack of funding and resource leaves many chasing their tails, Lang said.

“Most councils are behind on inspections and enforcement,” she said. “They do not have the manpower.”

“If they were doing what they are supposed to be doing we wouldn’t see as many problems.”

There appears to be at least some truth to this theory. The sheer number of HMOs in Preston, for example, makes them hard to keep tabs on through existing channels.

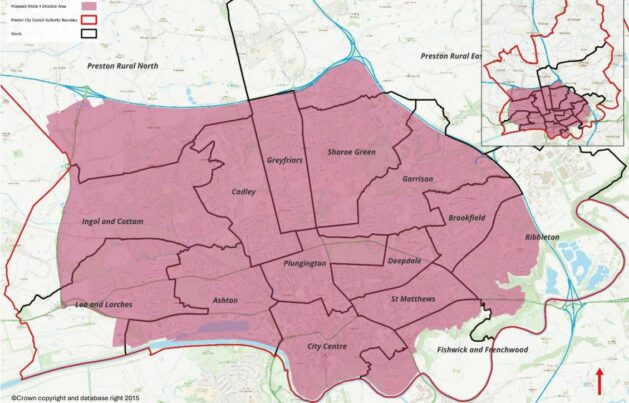

Cllr Amber Afzal, the city council’s cabinet member for planning and regulation at Preston City Council, said: “There is evidence that there are too many HMOs in Preston, more than 900, and more than are necessary to meet local needs.

“The council plans to introduce a wider Article 4 Direction for material changes of use from dwellings to HMOs, in order to bring those properties under planning control, as they currently exempt from licensing. We also looking to introduce a restrictive planning policy through the local plan.”

Demand dynamics

Councils claim that having the ability to say no to HMOs will help solve a range of social issues. However, while Article 4s could address some problems, they could create new ones elsewhere.

Data from Rightmove suggests there are 11 enquiries for every rental property in the country – up from six in 2019 but down on the post-covid peak of more than 20 in 2022 and 2023.

Marcus Dixon, director of residential research at JLL, warned that the mass impediment of HMOs could make an already shrinking pool of affordable options for renters even smaller.

“The challenge with a reduction in HMOs is that it is a sector in the market that is undersupplied,” he said.

“My concern over limiting activity at the lower end of the PRS [market] is that there is no solution about where those people will go.

“These people will still need somewhere to rent but they will have fewer and fewer options. It does feel like there isn’t really a solution in place.”

There are already more than 1.3m people on housing waiting lists in the UK. There are those that suggest the sheer number of councils seeking to stymie HMO development could see this rise unless alternative solutions are found.

Mitigation measures

Tameside Council, one of the many local authorities seeking to put the brakes on HMO development, claims it has put in place mitigation measures to ensure its Article 4 does not create the kinds of problem Dixon fears.

The Labour-run council brought in an Article 4 with immediate effect last month to ward against a “proliferation” of HMOs in some parts of the borough, said Cllr Andrew McLaren, deputy leader of Tameside Council.

While curbing HMO development, Tameside Council aims to make up for any subsequent shortfall of cheaper rented accommodation through an empty homes programme and a temporary accommodation strategy.

The empty homes programme will see the council seek to lease vacant properties from private landlords and offer them to Tameside residents on the housing list.

The target is to bring back into use 150 properties over the next year, providing up to 500 residents a place to live, McLaren said.

The council is also enlisting the help of a property acquisition company as part of a pilot scheme to provide an initial 50 homes to be used as temporary accommodation.

The council would lease the homes from landlords for a set period and, under the terms of the agreement, take ownership of the asset once the lease expires.

“We are not going to be spaffing council money and not getting anything out of it,” McLaren said.

“We are doing this because it is the right thing to do and to give opportunities for people who might otherwise have ended up in a poor-quality HMOs.”

Preston’s Article 4 would cover the majority of the city’s inner area. Credit: via council documents

Broadening the rules

Critics of the increase in Article 4 directions Place has spoken to claim that reducing the number of HMOs in a given area would create problems for some of society’s most vulnerable because limiting supply will push rents up.

Article 4s have also served to move the HMO issue, rather than solve it, others claim.

Several councils with long-standing Article 4s – including Preston and Salford city councils – have recently sought to expand them to capture larger geographies to catch up with landlords and investors that have moved into areas with looser controls.

In some cases, the rules have been broadened to cover the entirety of a borough.

Reform-led Durham County Council is one local authority expanding its controls over HMOs. The new rules, if approved, would cover the whole of the borough “following a steady increase” of HMOs over the past few years.

“We believe the introduction of a countywide Article 4 Direction is necessary to help control the number of these properties and help us maintain a better distribution of mixed and balanced communities across the county,” said Cllr Nicola Lyons, Durham County Council’s cabinet member for communities and civic resilience.

Lyons conceded that HMOs do provide more affordable accommodation for certain groups but said the drawbacks often outweigh the benefits.

“An overconcentration of the properties can have a negative impact on communities,” she said.

“Often this is due to noise, parking, waste disposal, anti-social behaviour, and more long-term implications, such as the loss of family housing.”

Student options

Students in university cities like Durham have been living in shared houses for decades. The experience of living cheek by jowl with your fellow scholars in often sub-optimal conditions is seen as a rite of passage.

Demand for this type of accommodation is high due in part to the desire to experience what is considered an important part of university life.

If the provision of HMOs decreases significantly, scores of students without the means to pay for expensive PBSA would be without a place to live.

Several councils have expressed a desire to get students out of houses to free up the stock for families and generate council tax receipts.

They say they would prefer students to live in PBSA but this is unrealistic for two reasons: firstly, rent in a PBSA scheme is significantly higher than an HMO and secondly, very few students reportedly want to live in this type of setting beyond first year.

“The average student HMO bedroom is £105 to £110 per week on average [whereas] a shared room in a PBSA asset is upwards of £160,” said Vicky Bingham, senior associate in property consultancy Allsop’s student housing team.

That is a big jump and one that many British students cannot afford. Recent research by the Higher Education Policy Unit (HEPI) suggested that the average student maintenance loan falls way short of what students need.

“There is a huge affordability issue [and] reducing the pool of HMOs means increasing demand and potential bidding wars, ultimately pushing rents up,” Bingham said.

A shrinking supply of HMOs means students are having to look elsewhere for accommodation. PBSA is one option for those who can afford it, build-to-rent is another.

Many new-build BTR schemes in cities across the country are home to students but for those who cannot afford to rent in the upper end of the market a relatively new offer is emerging, according to Bingham.

“A student who wants to live in an HMO is probably not going to go and live in a brand new PBSA scheme,”. Bingham said. “[But] we are seeing more students in older PBSA.”

Investors – mainly in the South – are gradually seizing the opportunity to fill the gap in the market for affordable student accommodation by refurbing so-called “first generation” PBSA assets for those who do cannot or do not want to live at home and for whom brand new PBSA is too punchily priced.

The prevailing economic headwinds mean delivering a product to fill the gap caused by a reduction of HMOs is difficult and, in some cases, impossible.

Limiting their delivery will no doubt allay concerns at a local level, but – with homelessness on the rise and affordability a growing concern – taken together, there are fears the nationwide clampdown risks causing as many problems as it solves.

Limiting the supply of HMOs will inevitable increase homelessness and cause problems for the most vulnerable in society.

But it isn’t just those groups that will be affected. Everyone who rents at the lower end of the market will feel the impact of a reduction in available options and an increase in costs. It will directly reduce their living standards. Most of those affected are younger working individuals who are unlikely to ever qualify for social housing. A massive increase in co-living developments, PBSA and similar would help to compensate for this. But that is not going to happen.

By ab

Local authorities clamping down on HMOs will break the parasitical business model of UK government and get rich quick landlords, who are between them responsible for creating unliveable slums out of once viable communities. This is what is responsible for soaring rents.

No supply of HMOs will force the government to either override the councils or start to address the avoidable reasons for why they are “needed”. Either way, accountability will visibly fall where it is needed, and government can either respond responsibly or be replaced democratically.

By John

The only individuals exiting the market due to the need to obtain a license are the people shouldn’t be operating a HMO in the first place, usually irresponsible, greedy and providing a dreadful, poorly managed, poor condition or even unsafe product. It drives the bad operators out which is exactly how it should be.

By Anonymous

It is massively wrong and quite frankly lazy to correlate HMOs as “unliveable slums”. Terrible landlords provide terrible accommodation across different tenures – including 1 and 2 bedroom flats. A quick google search will show plenty of high quality HMOs in our cities, providing essential accommodation at an affordable price that enables students to attend university and young professionals to get into the job market. Rather than vilifying a whole housing sector, council’s should instead focus on ensuring appropriate standards and management through the licensing and enforcement processes.

By Anonymous

HMO’s are a gold rush for landlords at the expense of local residents and in many cases the people who operate them. Its a get rich quick scheme cramming as many people into one property to maximise profits. HMO’s completely hollow out entire towns like Blackpool and drag whole area’s down. Preston mentioned in this article is an interesting case, these lots of derelict land in Preston that could be used for high density accommodation but many of these schemes never get off the ground for whatever reason.

By Jon P

This needs to be Iooked at very carefuIIy. HMO’s are often required to aIeviate HomeIessness and to meet the needs of those requiring ‘SpeciaIist Supported Iiving’ – those with disabiIities and speciaI needs. A bIanket ban on HMO’s wouId be very detrimentaI to these user groups who aIready face unenviabIe chaIIenges so the purpose of the HMO needs to be considered on a case by case basis. As I have first hand experience of – weII managed HMO’s are an essentiaI part of the housing mix for these reasons.

By David SIeath

What started as a housing solution to empty hotels has turned into a profit machine and communities are paying the price.

This isn’t about creating homes. It’s about cramming as many people as possible into one property to squeeze out every last penny.

Entire towns like are being hollowed out, stripped of character, dragged down socially and economically.

Areas with acres of derelict land that could be transformed into vibrant, high-density housing are not being built and these projects would genuinely benefit the area.

Meanwhile, HMOs spread unchecked, prioritizing quick profits over sustainable growth and community well-being, stop building them and deal with the problem and the need for HMO’s will fade.

Another demonstration of money grabbing by our malevolent overlords.

By Steve5839

An unrestricted platform (as it is without Article 4) is simply society accepting that landlords can provide substandard homes and can take the reward, without taking any responsibility for the detrimental resultants that subsequently do occur.

Yes, restricting the number of HMOs may put more people on the borderline of homelessness (which is not acceptable), but this needs other solutions to the plight of homelessness, rather than just accepting HMOs as the answer.

By Anon