The Subplot

The Subplot | Student housing, gigafactories and stadiums

Welcome to The Subplot, your regular slice of commentary on the North West business and property market from Place North West.

This week: North West student housing developers and investors fret about the return of high-rolling overseas students. Will new-build student housing be viable without them? Meanwhile, doubts about Vauxhall Ellesmere Port make hopes for a 6m sq ft gigafactory in the region feel more urgent. Is the region ready to grab the chance? And why 93 is the magic number for Everton’s newly approved Liverpool waterfront stadium.

MISSING YOU ALREADY

PBSA and its overseas student problem

PBSA and its overseas student problem

The North West’s purpose-built student accommodation sector hopes it can weather the Covid storm. Will the overseas students so many operators depend on come back?

A Middle Eastern investor is on the brink of a £60m student housing investment deal in Liverpool, and Manchester is digesting the latest student tower plan: Fusion Students has submitted proposals for a £40m Manchester development. Fusion and the unnamed Middle Eastern investor take the plunge at a tricky time for PBSA. Subplot was told earlier this month how the absence of overseas students unsettles at least one BTR developer. New-build PBSA has the same worries, magnified by the rental guarantees routinely offered to investors to maintain pre-pandemic pricing levels.

Good news!

UCAS data published last week on applications for university places starting in September 2021 shows that the feared Armageddon hasn’t happened: the total number of overseas student applications for UK universities is down only a little, from 116,000 to 112,000. No surprise that Brexit means the number of EU students has tumbled from 43,000 to 26,000 but they’ve been partly replaced by applications from the US (up from 4,140 to 6,670), India (up from 6,230 to 7,820) and, despite diplomatic tensions, from China (up from 21,000 to 26,000).

Tails are up

This is just what PBSA investors and developers hoped to hear. James Hanmer, Savills’ head of UK PBSA investment, is pleased. “Those were pretty good stats from China and India,” he says, insisting this overseas student issue is a blip, not a structural problem. Overseas students account for about one fifth of the student population, but approaching half the Manchester PBSA tenancies (more in London), yet developers are unshaken. “PBSA development is a two or three year play, and it is not even remotely a concern by the time the current crop of schemes get delivered,” Hanmer says. “If you offer high-end bedspaces, then so far bookings and rent collection has been remarkably robust because wealthy students make a beeline for places defined by service. On the other hand, operators with more generic studio-type products may struggle.”

Here comes the but

In the long-term nobody doubts the UK’s appeal to overseas students, but in the short- and medium-term it isn’t so obviously sunny. This soon becomes clear if you talk to StuRents, a student accommodation search platform that handles about two-thirds of the UK market. Says Richard Ward, head of research at StuRents: “Yes, demand is there from overseas students, but it doesn’t mean the students are turning up.” Ward points out that although UCAS harvested a bumper crop of applications that doesn’t translate automatically into either places, or actual arrivals in the UK, or high-end PBSA lettings, as experience during the 2020/21 academic year proved. If applicants don’t turn smoothly into residents then PBSA operators potentially have a problem. It is one their complicated relationship with the traditional student housing sector could make worse.

House share hell

StuRents data shared exclusively with Subplot shows both how dominant and how relatively cheap houses in multiple occupation are in Manchester and Preston (Liverpool is a slightly different story, see below). In Manchester there are 17,500 PBSA bed spaces and approximately 26,000 HMO bed spaces. In Preston it is 4,500 and 7,000 respectively. The price spread between PBSA and HMO is huge: in Manchester the average HMO bed is £110 per person per week (pppw), compared to £165-170 pppw for PBSA. In Preston the spread is from £80 pppw in a HMO to an average of around £120 pppw in PBSA.

Liverpool is different

Liverpool’s PBSA sector is relatively larger than Manchester’s: 22,000 PBSA bed spaces face 18,000 HMO bed spaces. A plentiful supply of PBSA beds means prices are, on average, lower. This in turn means the differential price spread with HMOs yawns a little less: HMO average is £95 pppw, compared to £130 pppw in PBSA.

What this means

Amber lights are flashing. Ward says that if you have an empty PBSA bed in Manchester or Preston your chance of filling it with a UK student is, on the strength of these numbers, seriously questionable. If the bed is in Liverpool your chance is just averagely uncertain. This could pose cashflow problems for operators and headaches for those backing rental guarantees.

Are investors bothered?

There are signs of caution. For instance, Cain International has been a big buyer, even during lockdowns. Late last year it agreed an £80m development loan to finance the development of a 780-unit Vita Group student accommodation scheme near the University of Warwick in Coventry. But Cain told Subplot that it is not currently looking in either Manchester or Liverpool. Others take a different view: Ares agreed a £157m PBSA deal just last week (not in Manchester). Barings is still buying, signing a £43.8m London and Manchester deal before Christmas.

Conclusion: Savills was predicting £10bn invested in UK PBSA in 2020, but the pandemic blasted many plans off-course. This year will see most of that money return.

DRIVING THE WEEK

The North West’s Gigafactory Moment?

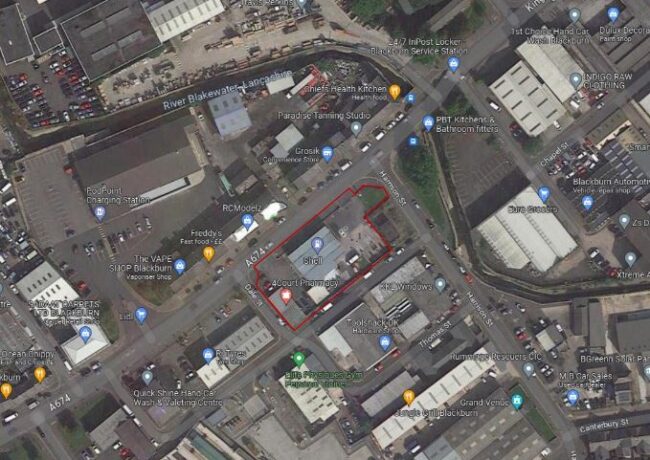

A decision is imminent on whether Stellantis, the Vauxhall-Fiat-Chrysler tie-up that operates Vauxhall’s Ellesmere Port plant, will keep it open in the face of new rules on electric vehicles. Can the North West grab a 6m sq ft gigafactory to smooth the transition away from petrol and diesel?

The “gigafactory” is one of the catchy ideas of US tech celebrity Elon Musk, and its purpose is to make batteries. Musk’s Tesla gigafactories have tended to be monsters: his first was 1.9m sq ft in Nevada. Musk says more than one hundred will be needed eventually. The UK government agrees they are the future and says up to £500m is available to help fund a new UK gigafactory. The West Midlands is already pressing ahead with plans (see below). Promoters say it might need to be 6m sq ft and employ up to 4,000 people plus spin-offs in the supply chain. Excitement is inspired by a global market for electric batteries expected to top $567bn by 2025.

Site options

England has, so far, only one live plan for a gigafactory and it is being promoted by Britishvolt for a 230-acre site at Blyth, Northumberland. The aim is for a 2.7m sq ft facility. Subplot asked Britishvolt what made a good gigafactory site. “Access to renewable energy directly from Norway, transport links – by rail, road and sea, and the speed at which we could break ground ultimately led to choosing Blyth,” a spokesman said. “Sustainability is at the core of the project and to be able to ship raw materials directly to the site via the deepwater port located in Blyth and use sustainable energy direct from Norway, was a large consideration.” Britishvolt added that the readiness of the site was also an issue. What it didn’t say, but others do, is that the proximity of an established automotive supply chain is fairly useful, subsidies and incentives matter a lot, and an ample and sustainable power supply with suitable heavy-duty site connections is vital (the Blyth site is a former power station).

Grab a gigafactory

Can the North West net one of these monsters? The region’s deepwater ports, local automotive supply chains and proximity to energy supplies (nuclear and Irish Sea wind farms), all suggest ‘yes’. However, there are three big reasons for doubt. First, there is a rival already ahead in the game. Last month Coventry City Council agreed with Coventry airport’s owner Rigby Group to promote a site for a 4.5m sq ft gigafactory. It already has regional backing and all the infrastructure and strategic planning cover anyone could wish for. This puts the North West at a disadvantage.

Learning experience

Second, the last time a gigafactory prospect wafted in the North West’s direction things went wrong. The Northern Gateway site close to junctions 18 and 19 of the M62 at Heywood was a surprise contender for the fourth and most recent Tesla gigafactory. Capable of providing 6.4m sq ft of floorspace it would have been ideal, one of perhaps only seven or eight sites in the UK that could take the requirement. But Heywood lost out to Berlin in December 2019. The disappointment caused local leaders to lash out at the government for fumbling the support package, but this factory was probably heading to Germany from day one. More usefully, the disappointment caused the region’s investment bosses to sharpen their thinking.

Is everybody ready?

Third, unfortunately the prep is not as far advanced as it might be. A search of Liverpool City Region paperwork revealed nothing, and the combined authority did not respond to a request to talk. In Greater Manchester the June 2019 industrial strategy gives battery technology a single name-check but a Combined Authority document search reveals very scanty references: it is fair to say policy work is thin on the ground. No sites have been specifically allocated for gigafactories. Tim Newns, chief executive of Midas, told Subplot: “Greater Manchester is preparing the ground for large advanced manufacturing, of which gigafactories may play a part.”

Hesitations

Policy and preparation might not be the only thing holding the North West back: there are also viability issues. Britishvolt is a start-up promoting a £2.6bn project, quite a jump from a standing start. Other potential operators cause landlords and developers (and public authorities) covenant fears on a similar, or greater scale. “You have to look at potential operators with some concern,” one very well-funded car-enthused developer told Subplot. “They have no history.”

Conclusion: Taking on a gigafactory may be the route to the future of the North West auto sector but today, in 2021, the North West has some thinking to do first.

IN CASE YOU MISSED IT…

Wishful thinking

The economic benefits of the newly approved 53,000-capacity Everton stadium at Liverpool’s Bramley-Moore Dock “far outweighed any harm it might cause” to the historic waterfront, said city planners. Really?

Like the dead-granny-on-the-roof-rack story, the idea that football stadiums have regeneration benefits is one of those urban legends that have a life of their own. It is retold and believed because fans need to believe it, and because common sense says very big things must have very big impacts. Unfortunately, common sense is misleading. The best you can say is that a significant regeneration benefit is unproven. “The hard evidence for a positive economic impact is still lacking,” said the London Assembly after a spate of big stadium developments in the capital.

Just 93 jobs

If we’re talking regeneration, and not the one-off hit of a big construction project or huge dispersed effects at the macro-economic level, you need to look at the long-term annual boost to gross value added (GVA) in Liverpool City Region. Subplot has read the economic impact assessment so you don’t have to (although you can find it here) and the stadium’s long-term benefit for Liverpool City Region amounts to no more than 93 direct full-time jobs and 16 in the supply chain. Once you include wages and additional visitor spending that’s GVA of £4.5m a year, which is small beer in a city region with GVA of £23.1bn. Yet to discover this puny outcome you would have to disinter the numbers from a lot of other confusing numbers about the city-region and wider North West, and learn to ignore a fair amount of what looks like double counting.

Those darn numbers

For instance, the analysis refers to GVA then makes separate claims about “direct additional spending” or “additional expenditure in the supply chain” – both of which are gross value added, aren’t they? And if they are not, why not? Then there’s “net additional wage income” which ought also to be part of GVA? An Everton enthusiast who added up all the numbers in the executive summary, without realising several of them are repeats, and not being sure whether North West regional benefits include or exclude Liverpool City Region benefits, might conclude that on even the narrowest view the stadium’s benefit to the economy was in the region of £34m annually for the city region and well over £100m for the North West. To repeat, it is £4.5m (and £9m for the North West).

Every little helps

To create some really big numbers the report then goes on to include the future development of Goodison Park, which is not part of this planning application. Both the construction phase and its outputs once completed are factored here and there are oddities. For instance, the assessment suggests 173 homes will “generate” 415 residents adding £7m annually to GVA. But it won‘t “generate” residents, it will simply divert them from somewhere else, and unless they assume migration into the Liverpool City Region (but not from the North West), how is this adding to the net additional GVA? Their assumptions on leakage and displacement (low) and multipliers (high) make the 250,000 sq ft non-residential element of the scheme strikingly optimistic. Yet more big numbers get added thanks to claims about a wider “catalytic” effect in the Ten Streets area which are hard to verify. The suggestion it will add £100m to post-construction phase GVA seems to depend on the volume of space with planning consent, which is to confuse hope with achievement.

Vote early, vote often

If you added up all the claimed benefits (and the report does not warn against this, despite the confusion over GVA, and what region we’re talking about) you would come up with a massive number: well over £500m. Actually. the report goes one better and claims “at least” a £1.3bn boost to the economy once you factor in social and general values (whatever they are). This is the kind of number that gets politicians to brush aside heritage concerns, particularly if elections are coming up.

The Subplot is brought to you in association with Cratus, Bruntwood Works, Savills and Morgan Sindall.

Do you actually understand the draw of the Liverpool Waterfront or pretending not to? In terms of build on the waterfront, Everton’s stadium is the bookend – and it’ll be for major concerts and events too. Physically it’s certainly more Sydney Harbour than Salford Quays. The prospect of this stadium is already transforming the Waterfront mile into town.

By Roscoe

Liverpool’s visitor economy is buoyant at weekends but there is vast spare capacity during the week. LFC currently help fill that void by attracting visitors in midweek, but with a local fan base Everton are unable to market games to a wider audience. Do not under estimate the power of the Premier League, and potentially European competition in stimulating the visitor/night time economies. The stadium also gives the city an opportunity to hold large none footballing events that are currently limited due to the unappealing locations of both the current stadiums.

By Graham Brandwood

@Roscoe I agreed the positive impact the Liverpool Waterfront stadium will have is huge both visually and beneficially, and I agree, Salford hasn’t got a patch on Liverpool Waterfront , I find Salford soulless and definitely instantly forgettable .

By Francis

I do enjoy Mr Thame’s acerbic observations but he must see that the Goodison Pk development – and it’s social benefits – are linked to the BMD proposals. They are two sides of the same coin. To quantify value in economic terms only is to know the cost of everything and the value of nothing. So, ner…

By Beetle juice

Anderson, as an Everton fan, wanted it. That’s as much as anyone can say about this with any certainty.

It’s a shame he didn’t put as much fervour into securing HS2, the Commonwealth Games, Channel 4, major civil service relocations, or indeed any other meaningful business for the city, during his tenure.

With that in mind, PNW waxing sceptical about the business benefits being sold to us is rather understandable.

By Jeff

Is this near the proposed rotating theatre of the world class ten streets district? Will this stadium rotate too?

By Edward Woolley

I wish Everton well, but a welcome sense check on economic impacts of these developments. If you look at East Manchester the Etihad ( Metrolink) is only just starting to trigger big moves like the Co-op Arena, and that’s 20 years out from the Commonwealth Games.

By Rich X

Sorry but my first post is not clear. Everton’s current capacity, poor facilities, and obstructed views do not allow the club to be marketed to a wider audience. The new stadium will enable the club to grow attendances, attract people from outside the regular fan base, and contribute to Liverpool’s visitor economy.

By Graham Brandwood