Commentary

COMMENT | How to fix the broken rural housing market

The last 20 years have seen a growing crisis in rural housing, writes Matthew Morris. The headlines regarding lack of supply and issues with affordability speak for themselves. Now communities face further challenges regarding the type and location of housing that is being built.

The last 20 years have seen a growing crisis in rural housing, writes Matthew Morris. The headlines regarding lack of supply and issues with affordability speak for themselves. Now communities face further challenges regarding the type and location of housing that is being built.

Councils have been slow to react to the changing needs of rural communities and the demands of the economy in the rural area and have failed to address the problem of housing supply in a way that protects those vital services that do exist.

The solution proposed by many Local Authorities is to build as many houses in as few ‘key settlements’ as possible. This brings inherent problems with tensions over site selection and a feeling that many villages are being swamped.

Large scale development risks turning the British countryside into a series of identikit villages marked by poor design and a limited choice of house types and sizes.

When the National Planning Policy Framework was introduced in 2012 it was the most radical reform to planning legislation in a generation. For communities in rural areas in particular it offered a lifeline, an opportunity to reverse problems exacerbated by protectionist anti-housing policies that had more place in the green belt than in open countryside.

It identified that small scale, gradual growth was possible and that all communities could participate in the nationwide delivery of homes, not just larger market towns and villages.

Thankfully, the recently published update to the NPPF continued to reinforce the view that all communities have the ability to contribute to sustainable development in order to support local services.

Crucially, the NPPF recognised that the use of a car was essential in the countryside due to a non-existent public transport network. Recent analysis has shown that 134 million miles of bus routes have been lost over the last decade and yet, some councils are using public transport as a binary ‘yes or no’ test as to whether housing can be built in a village or hamlet.

Not only is this contrary to the guiding principles of the Framework, but is also ignores the other services that these smaller rural communities often have to offer; the village shop, the pub, the church or the village hall. All essential and valuable parts of community life and all services that will wither and fail unless some gradual housing growth is allowed to happen.

These facilities will never be replaced, are often provided at no cost to the public purse and yet what we are witnessing is the gentle erosion of key parts of rural life and the services within it.

I am not advocating the whole-scale development of the British countryside.

What villages and hamlets need, and I believe would respond positively to, is a requirement for each place to deliver small scale, gradual growth – measured against a simple test that is provided within national planning policy – will it enhance or maintain vitality? – or in layman’s speak, is it going to make for a better place and increase quality of life for current and future residents?

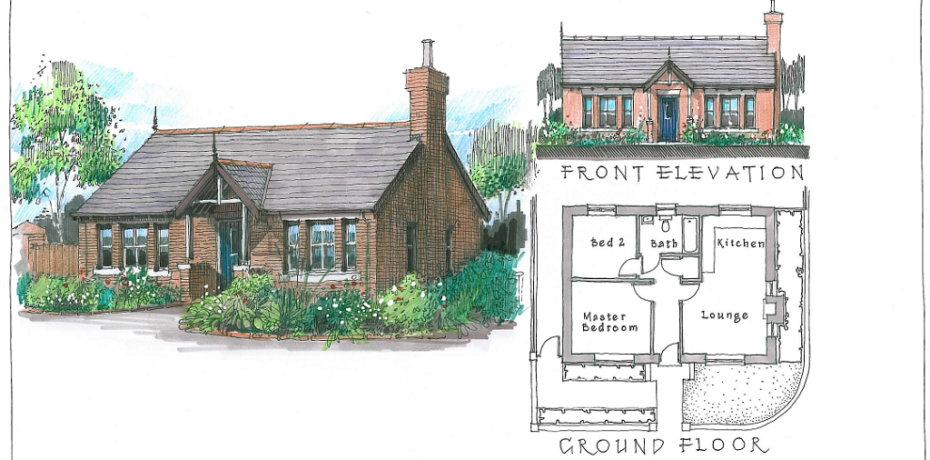

The right sort of development that meets the needs of the community in which it sits, sustaining local services for the future and providing additional Council tax income to support vital services. It might be starter homes for the young or bungalows for those people wishing to downsize in retirement. Crucially, it might be homes for rent or homes for sale.

Small scale can also be beautiful. Development can be well sited and sympathetic to the surroundings in which it sits and add to, rather than detract from, local distinctiveness through careful choice of materials and design palettes that are rooted to the community in which they sit.

Small scale can be built by local contractors who employ local people. Above all development can take place gradually and in a way that people would hardly notice.

If every community had to rise to the challenge; to provide development plans that enhance and maintain vitality of their settlements in order to deliver an element of growth, it would shift the debate from “not in my back yard” to “what do we want?”

The focus could then be on the need, design and quality, and above all the impact on the sense of place.

Rather than building to ever decreasing margins, uniformity and a ‘one size fits all’ approach, the right houses could be built in the right places. With each community able to contribute to the growth agenda without changing the face of the countryside.

- Matthew Morris is estate manager for The Bolesworth Estate in Cheshire. As a provider of rural affordable homes, Bolesworth was the first private landlord in the country to be recognised as a registered social landlord equivalent and has gone on to deliver a range of different rural housing

Well written and insightful, I agree entirely. If all small villages and hamlets were required to provide a small but suitable level of growth we would see vibrant and organic growth within our communities.

By QuaysMan