Place10: Sowing seeds of growth

Ten years ago, I watched with wide-eyed adolescent enthusiasm as Manchester’s cityscape transformed. Excitement and optimism were in the air, jostling for space amongst the cranes which littered the city’s skyline at the time, writes Ed Howe.

Ten years ago, I watched with wide-eyed adolescent enthusiasm as Manchester’s cityscape transformed. Excitement and optimism were in the air, jostling for space amongst the cranes which littered the city’s skyline at the time, writes Ed Howe.

When the economy collapsed, the property scene dried up and for a while, so too did my interest. But while my attention was side-tracked, Manchester was busy transforming itself with public investment instead; preparing itself for the next economic boom. The Metrolink expansion, MediaCityUK and the Northern Hub project kept the city’s construction workers busy but these weren’t just vanity projects or apartment buildings as had come before. These were seeds which would ensure that a strengthened Manchester could fly off the starting block the moment the economy recovered.

Howe is author of the Manchester Development Update – click here for August 2017 edition

So, when the clouds lifted once again in about 2012, that’s exactly what happened. A flurry of proposals ensured that this city powered ahead. It’s also when I started paying attention to property and urban regeneration again, charting the economic boom and collecting statistics on Manchester’s revival. In many ways the boom we’re currently seeing is bigger, more optimistic and more far-reaching than the last one. Our skyscrapers are taller, the benefits are more widespread and the investment is better directed. In 2007, the tallest building proposed for Manchester was Eastgate tower, at 188m. We’ve now smashed that with two proposals taller than 200m, one of which is actually under construction at Owen Street.

As well as the taller buildings it feels as though this time round the city has more substance. We have better city governance which now encompasses all 10 Greater Manchester boroughs; a tram network befitting a city of Manchester’s size, and a Mayor to act as our spokesperson. Manchester is a much more grown-up, more ambitious city than it was just 10 years ago. The public stir caused around the St Michael’s proposals demonstrate this perfectly. This is now a city whose people share a vested interest in ensuring that it thrives and prospers; a city of Mancunians who demand high quality development. Only the best for Manchester.

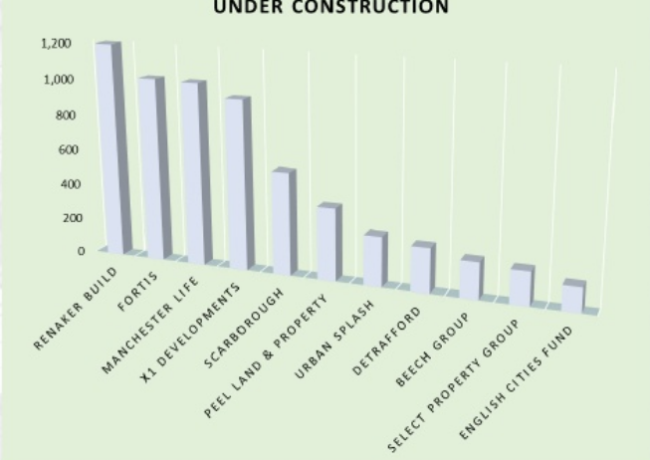

I’ve been collecting statistics on Manchester’s development and regeneration since 2012. Back then, there were just 275 apartments under construction across the entire city, including central Salford and Salford Quays. Now, just five years later, there are nearly 12,000 homes under construction, and a further 19,700 in planning. According to the latest population figures in 2016, Manchester had 20,800 people, a big jump from the 11,600 recorded in 2007. By 2021, the population of Manchester city centre is likely to exceed 50,000, and we’ll see similar rises in central Salford, Hulme and Salford Quays, too. All of this will enable the population of Greater Manchester to hit three million by the mid-2020s; which will represent a rise of 600,000 people since 2007.

Unlike in 2007, in 2017 we’re able to track, chart and map every single change occurring in this city and allow people to engage with it like never before. The number of apartments underway; the amount of office space and hotel beds planned and under construction are all recorded, and my interactive map demonstrates the spatial distribution of all the city’s schemes and proposals.

As we go forward into the next 10 years, it’s important that we continue to fund our infrastructure, electrify our railways and redevelop our transport hubs. Keep demanding the best for our city, and ensure that the property boom is felt by all Mancunians. Demanding the best for our city extends beyond our borders; assuring that Manchester and a more united North of England have a much stronger voice in Westminster. The recent cancellation of the electrification programme shows how Westminster sentiment towards the North of England has not changed as much as we’d originally hoped under Osborne’s Northern Powerhouse. Most importantly, I believe, we need to unite with our neighbours in Lancashire, Liverpool, Cheshire and Yorkshire to produce strong and robust business cases for vital Northern infrastructure projects which would totally transform our city and our region.

- To take part in the Place10 series reflecting on the decade since Place North West was first published in August 2007, send your stories and memories to news@placenorthwest.co.uk headed ‘10’.

Salford is not part of Manchester and Media City is in Salford.

By Phil

@Phil I’m sorry, but that old mentality has got to die. Yes, technically speaking, Salford is not within the boundaries of the City of Manchester. But, increasingly, it is seen as part of Manchester and I, for one, am perfectly fine with it; Westminster, Camden, Chelsea and Kensington are all parts of London even though the are not in the City of London.

The Point is: We must stop being overly padantic and unify behind one name!

By Alex.B

Sefton is not part of Liverpool and the Grand National is in Sefton (Lancashire).

Westminster is a city in its own right and not “London”. Parliament is in Westminster not London.

By Pointless pedant

Sefton, Lancashire? Pointless pedant seems to be living in the past…

By Abots

Alex if you ask the people of Salford (those born/bred), they will gladly tell you they dont seem themselves as part of Manchester, they see themselves as Salford. And why should we all unify behind one name? How boring is that

By CitySpotter

Agree with Alex B. Such a parochial mentality from Phil. All that separates these places is a small river. Both cities have benefited from the other but let’s be honest here, Salford has ridden on the back of the name of Manchester. Both form part of the well known conurbation of ‘Manchester’. The more they are unified the more prosperous both will be.

By Get over it

London’s geographically the smallest city in the UK. Could go on all day.

For all intents and purposes, Salford is a part of Manchester, as is Media City.

By Spock

Let the non-accountable neoliberal brainwashed government employees steal your identity. Let them tell you that you are no longer Cheshire born and bred, or no longer a Lancastrian but you are, from now on, an inhabitant of, say, Tameside, whatever that is. Let them close down your town hall, council offices, swimming baths, local school, police station, neighborhood shops, post office, and so on. Then wonder why you have no sense of belonging to a community or involvement in the place you live. Your life consists of work, commuting, home/garden, tv and your kids schooling. Don’t forget to move house regularly so your children learn early on what being uprooted is like. When they grow up they will be just like you. Rootless.

By A Lancastrian

I agree that over-parochialism hold Manchester/Liverpool back,but Central Manchester and Salford are getting all the money for housing from the fund. How much is Bolton or Rochdale getting to help improve the public realm?

By Elephant

@ A Lancastrian – its all about the economy. Without an economy there are no jobs, without jobs there is no livelihood and without the means to provide people with a livelihood, keeping an area shackled to a single identity is pointless. You can call yourself a Lancastrian or align yourself to Cheshire but functionally, your area is likely to be part of either Liverpool or Manchester. So for efficient and effective governance, cities are defined by first and foremost by their economic relationships. That doesn’t mean that identities can’t overlap or co-exist but to deny those fundamental economic relationships is to deny the reality of how places function. The closure of public facilities is a separate issue more to do with central government austerity policies than the functioning of the local economy.

By manc

Herehere, Manc.

Lancastrian – would it really help Liverpool to keep calling it part of Lancashire? I don’t see how referring to places by their relationship to the nearest urban conurbation undermines their existence. Places are in a constant state of flux – cities don’t just appear, they undergo a period of growth during which they experience inward migration: this is usually a sign places are doing well, look at Liverpool or Manchester in their heyday (although you could say Manchester’s heyday is really today). Places grow and attract people and THEN establish an identity… if places fall on hard times, the population stagnates, there isn’t much change and places become inward -looking: look at Liverpool in the 1980s and the cementing of its identity.

This isn’t a political question; a “neoliberal” conspiracy as you portray it. As Manc says, its all about economics.

By Spock

The ones whining about their borough of GM not being apart of Manchester sound just like old prunes. Salford is part of the Manchester city region, as is Tameside etc. I for one am from one of the GM boroughs but fiercely identify as Mancunian.

I’d be interested to know how Lancastrian etc voted in the EU ref, their narrow-minded, primitive logic on GM is a clear indication!

By Soya

Unlike Merseyside which has always been an economic entity,except for St Helens, linked by both sides of the river. Manchester,was never a Mother city to the towns North of it. This is the difference. In part this is due to Liverpool having a commuter belt on the Wirral and an Underground. Manchester was just the biggest place in South East Lancashire. Nobody in Oldham refers to Manchester as town for instance. Liverpool was always more like London, fed by satellite towns.

By Elephant

That’s nonsense Elephant. Where do you think cotton that was spun in Oldham went to? Where was it dyed, processed, marketed and sold? Who did the engineers, mill owners and logistics firms trade with? It certainly didnt all occur within Oldham. Different bits were done in different parts of GM with the higher order financial, engineering, scientific, marketing and selling functions located in the centre of Manchester, just like any other city.

You’ve fallen into the same trap as Lancastrian separating a narrow and individual perspective of identity from economic processes. The whole of Greater Manchester was a coherent economic system. The only difference between industrial era GM and modern day GM is that more workers commute into Manchester nowdays rather than in their individual towns for work, reflecting global changes in business practice and employment. But it doesn’t change the fact that (Greater) Manchester is and always was a coherent functioning economic unit – a city.

By manc

Manc you may be right about the different roles played by specific towns,but Manchester was never a Mother city for the Milltowns.At least not for ordinary workers.

By Elephant

Youve dont it again, Elephan, you’re confusing identity and economic processes. Manchester was indeed the ‘mother’ city due to the type of higher order functions it carried out within the total system for producing cotton goods. Just like any other city, it was the commercial centre carrying out higher value added functions in finance, marketing, selling, distribution, engineering, science and research as the processing of cotton was exported from the centre to cheaper out-lying areas. You see the same relationships between the centre and dependent satellite towns in cities all over the world.

So of course Manchester was the ‘mother’ city for the mill towns because they were dependent on Manchester for their competitiveness, for access to information, for access to value adding parts of the process and for trade.

By manc